Of Mice and Mountains: A Swartberg Roadtrip

Last week was a whirlwind. On Monday I was in the green and gently rolling hills of Dorset, England in the beautiful old Victorian house where I grew up. It was early summer, the buttercups were flowering and even the sheep were smiling. I left with great reluctance after a break that was all too short. By Tuesday night I was curled up on the floor sleeping in a small frozen heap in Doha airport in Qatar in the Middle East.

Wednesday night brought me back to a cold and wintery Cape Town. Exhausted, I was thrown headlong into the chaos of the Department of Home Affairs where the international residents of South Africa go in their hundreds crowded like cattle for visa applications and renewals.

By Saturday I was on the road again for the weekend in the name of pollination biology research. Our destination was the Swartberg Mountains, a little more than 400 km east of Cape Town. This rugged range towers high over the small ostrich farming town of Oudtshoorn to the south with the wide-open, sparsely populated semi-arid plains of the Great Karoo extending northwards.

Above: Protea lorifolia. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

We three made good progress eastwards along Route 62 squished inside the ‘Jimny’: a tiny underpowered box on wheels carefully disguised as a 4×4. Immediately after driving under the stunning rock arch of Cogman’s Kloof near Montagu, I spotted a huge snake crossing the road and we quickly u-turned and stopped to make sure no motorists ran over it.

Mr Snake was one of the largest puff adders I’ve ever seen at nearly a metre in length and we watched carefully as it continued its journey safely into the grass at the verge. Puff adders have highly cytotoxic venom and are responsible for more deaths on the African continent than any other snake.

That said, encounters with this beautiful snake are rare and a privilege at a safe distance where they will not feel threatened or cornered and be likely to strike. They should be treated with the respect any living creature deserves and are a vital part of the ecosystem to which they belong.

Top: Klipspringer. Above: Orange-breasted Sunbird. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

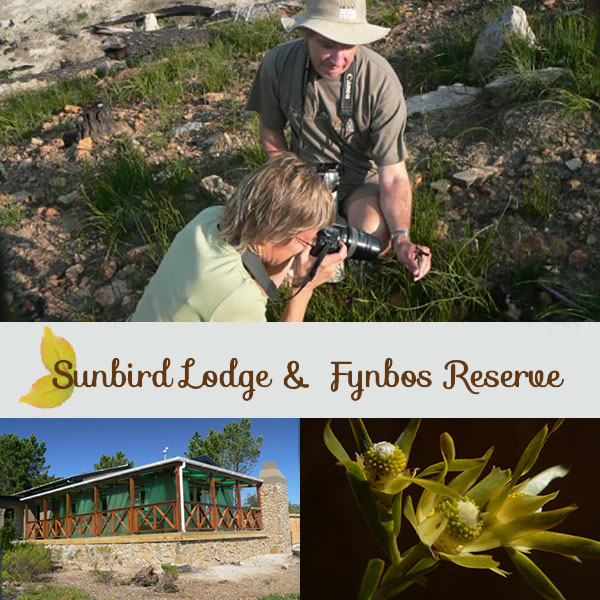

After a long drive west, we overnighted in the small Karoo town of Prince Albert before an early morning start for the main business of the trip. We were there to collect some camera traps from high in the Swartberg Mountains placed as part of a pollination biology research project.

Camera traps are movement triggered cameras that automatically take pictures of any living critter that happens to walk past them. They have a variety of different applications in biological research and can provide valuable information to scientists on everything from population distribution to the behaviour of mammals and birds.

They are particularly useful when stationed in remote or inaccessible areas and generate footage easily without the disturbance caused by the presence of a human researcher.

Top: Lower reaches of the Swartberg Pass. Above: Message loud and clear. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

In this case, we were collecting cameras that had been placed to monitor and provide new insights into the pollination biology of altimontane Proteaceae species. The species being studied grows high up in the Swartberg and is thought to be pollinated by mice.

However to date unsurprisingly nobody has been crazy enough to sit up there through rainy days and chilly nights to confirm this ‘educated hunch’ and camera trap film footage promises to provide new ecological insights into exactly who visits this species during its flowering season.

This is thought to be one of a number of Protea spp. which is adapted to facilitate rodent pollination. Other examples include Protea humiflora and Protea amplexicaulis. Rodent pollinated Proteaceae can usually be distinguished by their low hanging flowers and often yeast-like odour.

Above: Protea montana. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

We took the dirt road out of town towards the base of the Swartberg Pass which led us as close as possible to our high altitude field site. This 24 km stretch of dirt road ascends from adjacent to Prince Albert southwards over the Swartberg Mountains climbing to an altitude of 1,575m asl along a series of beautifully designed switchbacks.

The road was engineered by Thomas Bain and built by 250 convict labourers, being opened to the public in 1888. Some paid the ultimate price for their hard work during the second winter of the construction when the roof of one of their camps collapsed under the weight of snow.

Much of the road was constructed using perfectly dovetailed dry stone walls which are immaculately preserved to this day more than 120 years later. The Swartberg Pass is a National Monument and was the final road that Thomas Bain engineered in the Cape. It is also one of the greatest achievements of his career.

Above: The long and winding road: View northwards over the Swartberg. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

As we ascended up the pass early on Sunday morning we were treated to the sight of no less than five klipspringer. This beautiful antelope stands only a little more than half a metre in height and their name when translated from Afrikaans means ‘rock jumper’. Remarkably they derive all the moisture they need from the vegetation on which feed and never need to visit water to drink.

As we drove slowly upwards we were rewarded with views over some of the most spectacular geology in the world where the sandstone of this mountain range is contorted into a myriad of anticline and synclinal folds more than 120 million years old. Slowly as we climbed upwards the vegetation changes with splashes of pink of the last few flowers of the year of Protea punctata being visited by numerous orange-breasted sunbirds.

Above: Standing atop the Swartberg Pass buffeted by icy cold winds with the Swartberg foothills spread out far below. Photo © Zoë Chapman Poulsen.

Eventually, we arrived as ‘Die Top’, the summit of the pass and the start of our ascent on foot. We made steady progress up the steep and rocky trail typical of most in the Cape mountains through stands of Protea lorifolia with their pale yellow and pink flowers.

The wind was bitterly cold and scattered grey clouds flew past us at the same level as we climbed upwards. Our reward was stupendous views in all directions throughout the Swartberg range and beyond as we arrived at the research site to collect the cameras.

The winding road where we started was visible far below us as we sat hunkered down beneath the rocks out of the wind. We paused briefly to take a photograph to mark our achievement before beginning the long journey homewards, with luck armed with new information about the ecology of these achingly beautiful mountains of the Cape.

Find me on Instagram

Plant Information

Connect on Social

Connect on Facebook, Twitter and Instagram

Taking Action

There are many environmental organisations based in Cape Town and beyond that require the services of volunteers to undertake their work. So if you have a little time to spare please get involved.